Research

We are broadly interested in how patterns of genetic variation — across space and in time — are shaped by population structure, demography and polygenic selection. Specific research interests include:Barriers to Gene Flow and Speciation

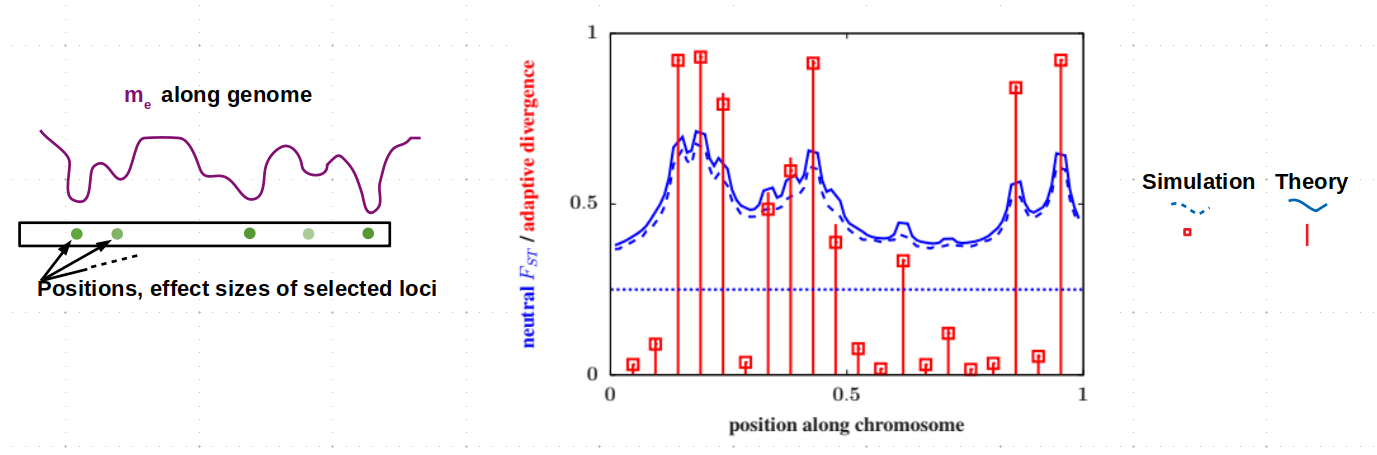

We are interested in the processes and genes that contribute to the breakdown of hybridisation and gene flow between populations during speciation. Specifically, we use models to understand how selection acting on multiple genes influences genetic and phenotypic differences between speciating populations, and the extent to which patterns in genomic data can provide information about the mechanisms and genes involved in speciation. A key question here is: (when) do individual genes matter? Conversely, do patterns of differentiation depend only on a feweffectiveparameters that capture the combined effect of many different barriers to gene flow? By identifying the parameters and genetic details that can(not) be inferred from data, we hope to gain a better understanding of the limits of genomic inference. More on this here, here, and here.

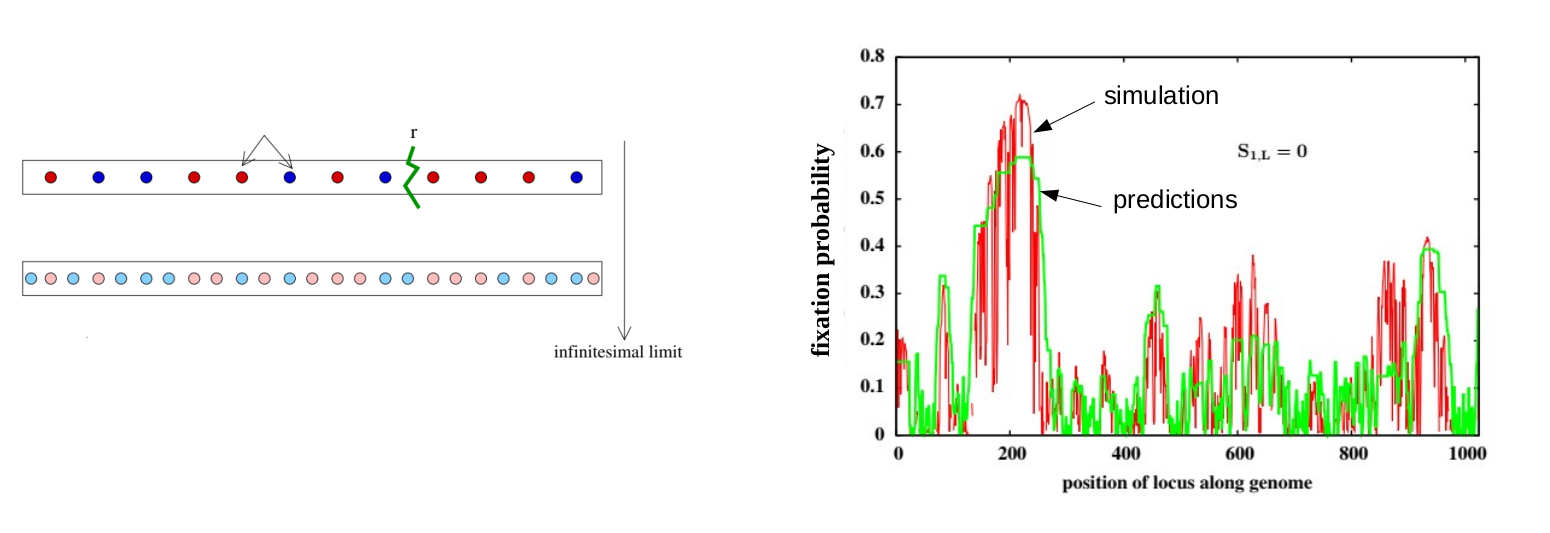

Linkage between genes and the response to selection

Quantitative genetics, which is the classical framework for describing short-term evolution, assumes that traits are influenced by many small-effect genetic variants that are unlinked, i.e., inherited independently of each other. However, in most organisms, genes are physically linked along chromosomes, with large chunks of chromosome passed on intact from parent to offspring during reproduction. We are interested in understanding the consequences of such linkage for the response to selection. A key question here is: does selection 'see' individual genetic variants or only large blocks of genome containing many such (beneficial and deleterious) variants. Furthermore, can we identify selected blocks in genomic data, and what can we learn from them about the strength and targets of selection? More on this can be found here and here.

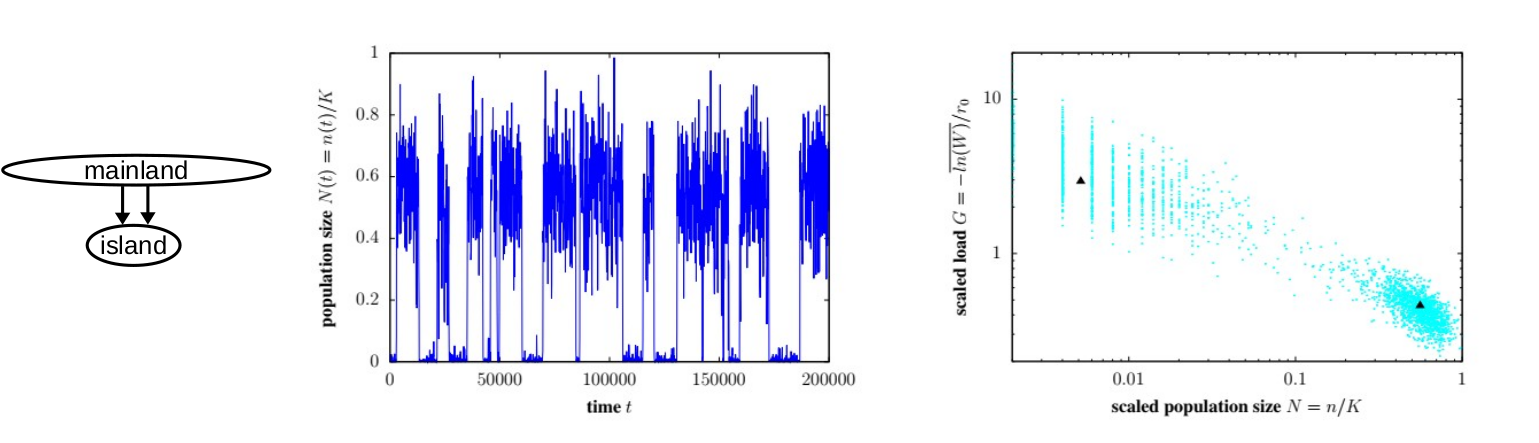

Eco-evolutionary feedback and population extinction

Most models of evolutionary change assume that the size of evolving populations is constant or determined by demographic processes, independently of the genetics of the population. However, this assumption breaks down in small or fragmented populations, which tend to accumulate harmful mutations at a higher rate, which reduces population fitness and size, which further accelerates the accumulation of harmful variants. This can result in a positive feedback betweeen declining population sizes and increasing genetic load that may eventually lead to population extinction. We aim to better understand such eco-evolutionary feedback using more realistic models that account for both genetic and demographic fluctations as well as polygenic fitness differences. The goal is to quantitatively characterise the conditions leading to extinction of fragmented or peripheral populations across a range of scenarios involving both inbreeding and environmental maladaptation. More on this can be found here, here, and here. In addition, we are starting various projects that focus on the genomic signatures of polygenic selection in spatially continuous populations,

with the aim of better understanding if/how different evolutionary processes can be distinguished in genomic data. More information here.

In addition, we are starting various projects that focus on the genomic signatures of polygenic selection in spatially continuous populations,

with the aim of better understanding if/how different evolutionary processes can be distinguished in genomic data. More information here.